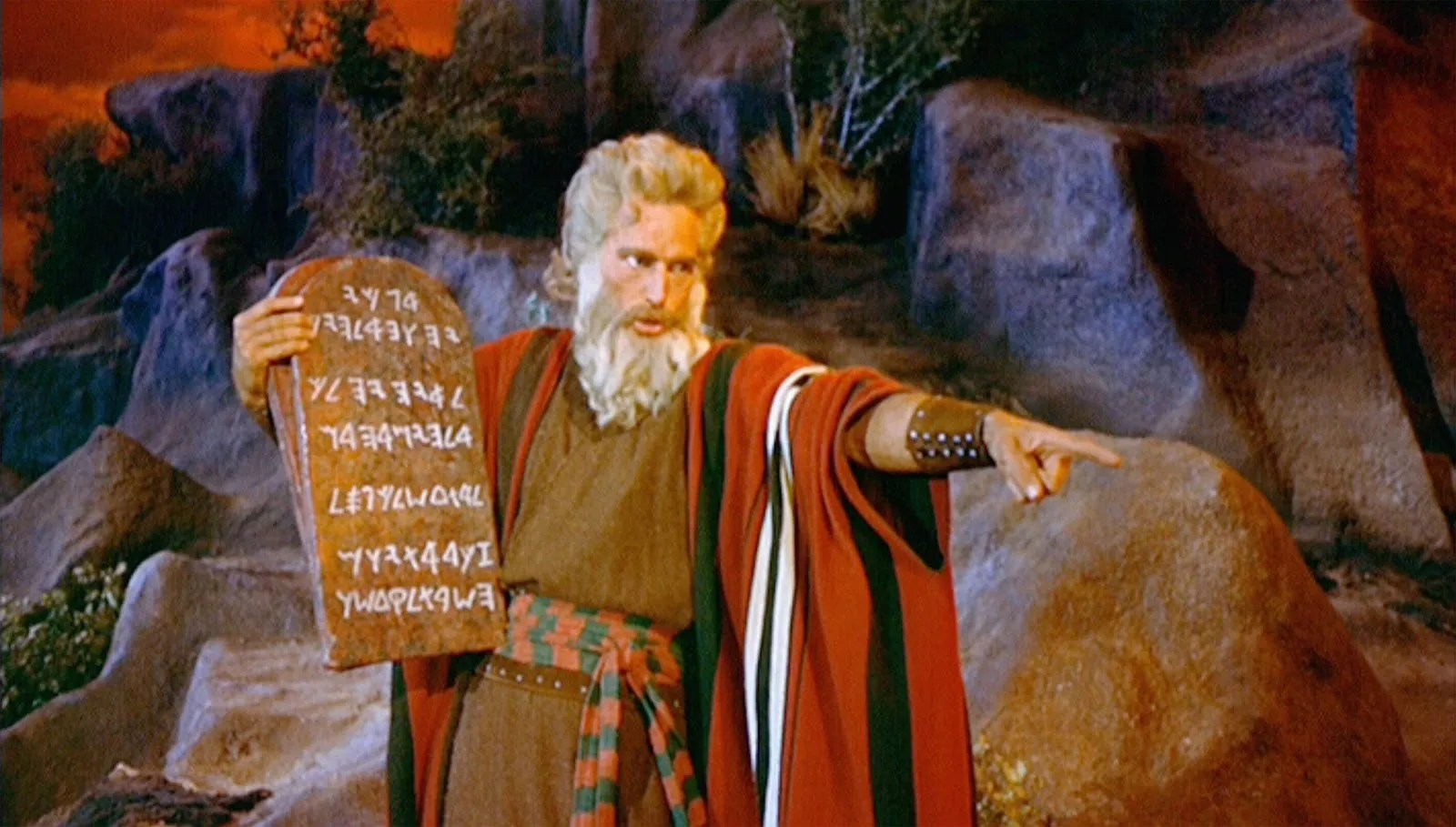

Lesson 5: The Moses Story – Part 2

The Moses story is not only that God frees the Israelites from slavery and genocide, but also that he creates a nation by giving them their own land and teachings about just ways to live in it.

The Moses story is not only that God frees the Israelites from slavery and genocide, but also that he creates a nation by giving them their own land and teachings about just ways to live in it.

I was caught off guard when discussing these social teachings in our Monday night gathering. My intention was to indicate they provided some guidelines for discerning God’s Word in our time. Ancient people were starting to perceive the orders of creation that make for a healthy society, such as insisting on two witnesses and limiting retribution to an eye for an eye.

Participants argued that they regarded these teachings as more harmful than helpful because they used God to justify and enforce human prejudice. The order I was approving really supported social ranking that preserved the privilege of the powerful. They were especially troubled by how they kept women in a lesser place.

On reflection, I had to acknowledge that the Bible reflected this conflict. Exodus 19- 23 supported my thought that the law promoted justice in community decisions. It begins by prescribing fair treatment of slaves. It goes on with protection for the weak: slaves, widows, orphans, aliens living in your midst, poor seeking loans, women caught in compromising situations, animals, and the earth.

Justice meant considering the circumstances and situation of actions. It included distribution as well as equity: gleaning so the poor and animals have enough, no interest charged for loans. And there were even Good Samaritan laws: returning someone’s lost animal, not returning an escaped slave, feeding a working ox.

The Deuteronomy 19- 26 rendition of these teachings is more concerned with maintaining the purity of the community. It begins with cities of refugees that provide a way to cast out evil, even when it is done accidentally. It purges the community of lepers and all sorts of people they considered contaminating society.

Those who challenged my rosy reading pointed out preserving the purity of the community really was a defense of privileged male power. It carefully defined a subordinate role for women. It justified genocide In warfare that brought spoils to the powerful. It claimed God approved the execution of any who challenged the status quo.

Obviously, we still must deal with this conflict between justice and purity. One side argues for casting out illegal immigrants and the other insists they have the rights of due process. One justifies genocide in warfare to eliminate terrorists and the other calls for protection of the innocent. One claims heterosexual marriage is essential for a healthy community and the other that faithful homosexual relationships are equally acceptable.

The conflict between justice and purity still haunts us.

Frontline Study is an online discussion of the scriptures, inviting you to share your comments and your reflections on each weekly topic. Simply click on the "Add Reply" text at the top of each post to see what others have posted and to add your thoughts.

Frontline Study is an online discussion of the scriptures, inviting you to share your comments and your reflections on each weekly topic. Simply click on the "Add Reply" text at the top of each post to see what others have posted and to add your thoughts.

I appreciate the uneasiness that some of your Monday night friends expressed. But I believe that it’s important to eat the fish and throw away the bones when reading passages in the Hebrew scriptures that we may find offensive. If we accept that scripture is inspired, and especially if we believe that Jesus is the Christ and hence reveals divine nature, then it seems clear (to me, at any rate), that principles which privilege the disempowered and promote justice, mercy, and love are the fish, and acts that run contrary to them are the bones. These scriptural teachings, when read discerningly, are the moral/spiritual foundations of Judaism and Christianity; how can they do more harmful than helpful? Granted, some Christians latch onto text-bones and use them to justify wicked actions and policies. But this is a misuse of scripture that’s easily called out by referring to the text-fish. One final point and then I’ll hush. I think you’re right, Fritz, to point out that it’s probably inevitable that bones and fish at times will be honestly confused or deliberately misused. But I think that the very scriptural inclusion of acts we find morally repugnant is a catalyst for us thinking deeply about the fish-bone distinction and, moreover, questioning our own cultural fidelity to purity, power structures, canceling, and so on: forms of oppression that may be so regular a part of our landscape that we have as much difficulty seeing them for what they are as the ancient Hebrews did in seeing theirs.